Why Does It Cost So Much to Live in California?

In the late 1980s, I visited Bombardopoulos, a small town in Haiti, with a dozen friends from my church. We worked alongside several Haitians on some community improvement projects. On Sunday, we visited the town’s church. We were stuffed into a hot and humid building, packed on backless wooden benches, so tight we were sharing sweat. As I watched the local folks on the bench in front of us who were packed more tightly than we would tolerate, it occurred to me that the idea of “personal space” means different things in different cultures. These people were packed so tightly they could barely get two cheeks in contact with the bench. I’d guess that the bench they filled with a dozen people would have fit only five average (plus-sized) church-goers in the US. As I sat admiring their sense of community another man entered that row, sliding step by step to a spot that he apparently deemed acceptable. I saw a problem developing. As he lowered his butt towards the already-filled bench, to my amazement, a space appeared. It was like the parting of the Red Sea. Somehow, he fit and nobody complained about it.

I often think of this picture when I read and hear Petalumans talking about the housing shortage in our town and region. Many people believe Petaluma is full. Traffic is unbearable. Water is scarce. Crime is worse and our town is losing its “charm.” We’re losing our personal space. Our sense of well-being is threatened every time a developer proposes a new apartment building or housing project.

But those feelings are relative. We can change our perspective. As uncomfortable as it may feel, we can slide over and make room for those who have come behind us. Think of all those before us who are sharing their roads and parks with us. Because of their sacrifice – voluntary or not – we can enjoy the quality of life that we know in Petaluma. The only way to repay that debt is not to go back in time but to slide over and make room for a few more.

The Bay Area “housing crisis” is not a crisis at all for California homeowners and that is why we don’t solve the problem. What is a crisis for lower and middle-income people is a profit-making machine for home-owners. We need to change our attitudes and recognize that until all of us are doing well, none of us are doing well.

This Petaluma home (3 bd, 2.5 ba, 1,806 sq ft) sold for $440,000 in 2010.

It’s now valued at $780,000 (2021). What is a crisis for many, is money in the bank for homeowners.

Oops, make that $864,000 (Aug 16, 2021), thanks to the pandemic migration and shortage of housing and building materials.

The housing crisis separates the haves from the have-nots. The haves are in a metaphorical lifeboat. They’re safe; their crisis is over. Around them are those struggling to find a home they can reasonably afford. For them, the scarcity of this most basic need constitutes a life and death crisis. They don’t have time for a perfect solution – a home built by a charity specifically for their income group, that does not impact traffic or the environment and satisfies all neighbors and interest groups.

What follows is a disjointed collection of articles about the “housing crisis” in the Bay Area.

Update Oct. 6, 2021

What’s Driving the Huge U.S. Rent Spike?

Rent increases of 20% or more are making life difficult for low-income tenants in many cities, just as eviction bans and unemployment relief are running out.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-05/tenants-struggle-with-red-hot-u-s-rental-market

Why Is California So Expensive? Housing!

Californians have to pay an exorbitant portion of their income for housing, leaving little for other expenses like food, transportation, education and savings.

This study, reported in the San Francisco Chronicle, estimates the true cost of property in the Bay Area. The article summarizes the problem in the first paragraph and gives the top three reasons housing is so expensive in CA, but particularly in the SF Bay Area.

The Bay Area needs to build over 440,000 units of housing between 2023 and 2031 to keep pace with its population, an average of nearly 50,000 units a year, according to the Association of Bay Area Governments. But over the last three years, it’s constructed an average of under 25,000 units annually. That’s because the region is one of the hardest places in the country in which to build homes, thanks to restrictive zoning, intensive permitting procedures and state laws that have historically allowed local groups to block residential development.

The study found that “zoning tax” costs property buyers and extra $409,000. Clearly, that far exceeds the ability of lower and middle-income residents to buy property and probably affects rental costs as well.

The researchers called the difference between how much land actually costs and how much it would cost without restrictive zoning the “zoning tax.” It’s not actually a government tax — just the estimated amount that artificial supply constraints, like zoning laws and permitting delays, add to the price of land across different metropolitan areas.

In a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the researchers found that in the San Francisco metropolitan area (which includes San Francisco, Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin and San Mateo counties), the median “zoning tax” for a quarter-acre of land was $409,000 — more than four times the region’s median household income.

The California Dream Is Dying

The once-dynamic state is closing the door on economic opportunity. By Conor Friedersdorf

This essay in The Atlantic details the ways California has gone from a land of promise and opportunity to slamming the door on future generations by allowing older Californians in the form of neighborhood home owner groups to largely shut down new housing of all kinds.

I fear for California’s future. The generations that reaped the benefits of the postwar era in what was the most dynamic place in the world should be striving to ensure that future generations can pursue happiness as they did. Instead, they are poised to take the California Dream to their graves by betraying a promise the state has offered from the start…

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/07/california-dream-dying/619509/

Today matters are much worse. The most powerful factions of residents do not want their state to grow and do not accept the fact that it surely will. For 40 years, they haven’t just failed to adequately plan for the housing needs of California’s current population; upper-income residents in San Diego and the Bay Area as surely as those in Los Angeles have deliberately fought to restrict the supply of housing. Even now, when housing costs are the primary reason that a majority of registered voters say they’ve considered moving, and when politicians in both parties pay lip service to the problem, there is insufficient political will to attempt a plausible solution. And the forces paralyzing the state are all the more entrenched because some of them believe themselves to be protecting the California Dream.

I feel the pull of their backward-looking vision. Years ago, I spent two glorious seasons in the Sea Ranch, a 10-mile stretch on the rugged coast of Sonoma County where beaches strewn with mussels rise to majestic bluffs; then to meadows where deer frolic and sleep; and, just beyond, hills of redwood forest that thrive in the fogs that roll in many evenings. If 50 million people could sustainably inhabit a state where all coastal development resembled the Sea Ranch, I’d sign up. In that fantasy, San Franciscans would all live in detached Victorians and Angelenos would all reside in prewar bungalows. Central Valley farmers could use all the water they wanted on their crops without affecting commercial fishermen, who could catch all of the fish they wanted forever. There would be no lines at Disneyland.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/07/california-dream-dying/619509/

Those expectations, fantastical as they sound today, seemed plausible within living memory. The Inexhaustible Sea was published in 1954. Around 1970, the Sea Ranch was considered a model of sustainable development. On rainy winter days in my 1980s youth, there actually were no lines at Disneyland. I once went on Space Mountain 18 times in a row, finding no one in line each time the roller coaster ended. Imagine if, in middle age, I felt entitled to pass laws so I could keep doing that into my 70s and 80s, no matter how many kids never got a turn. That is the anti-growth Californian, mistaking nostalgia for justice…

The rising generation’s charge, whether on behalf of the country, the blue-state model, or the tens of millions who’ll make their home in the state, is to make California exceptional again.

The Homeowner Revolution: the Shift to NIMBYism

Friedersdorf explains how local homeowner groups became so powerful and shut down housing in wealthier neighborhoods:

The hardship and misery the not-in-my-backyard impulse has inflicted on vast swaths of postwar Southern California trace their origins to 1964, when a man named Calvin Hamilton began his long tenure as L.A.’s planning director. At the time, his profession was grappling with critics like Jane Jacobs, whose The Death and Life of Great American Cities excoriated the hubristic urban-renewal projects of the 1950s for destroying whole neighborhoods, many of them populated by disenfranchised groups. As 1965 began, Hamilton embarked on an ambitious effort to gather feedback from 100,000 Angelenos (ultimately reaching a still-impressive 40,000) on how they wanted the city to evolve. The Watts riots of 1965 and continued unrest over the next three summers underscored that the Black residents of South L.A. needed to be heard. And the turmoil stoked the anxiety of white Angelenos, many of whom harbored the racial prejudices of their day and sought greater agency over “their” neighborhoods.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/07/california-dream-dying/619509/

Come 1970, there was broad support for a portentous shift: Los Angeles would abandon the top-down planning that prevailed during a quarter century of postwar growth in favor of an ostensibly democratized approach. The city was divided into 35 community areas, each represented by a citizen advisory committee that would draw up a plan to guide its future. In theory, this would empower Angelenos from Brentwood to Boyle Heights to Watts.

In practice, it enabled what the Los Angeles land-use expert Greg Morrow calls “the homeowner revolution.” In his doctoral dissertation, he argued that a faction of wealthy, mostly white homeowners seized control of citizen advisory committees, especially on the Westside, to dominate land-use policy across the city. These homeowners contorted zoning rules in their neighborhoods to favor single-family houses, even though hardly more than a third of households in Los Angeles are owner-occupied, while nearly two-thirds are rented. By forming or joining nongovernmental homeowners’ associations that counted land-use rules as their biggest priority, these homeowners managed to wield disproportionate influence. Groups that favored more construction and lower rents, including Republicans in the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce and Democrats in the Urban League, failed to grasp the stakes.

The Federation of Hillside and Canyon Associations, a coalition of about 50 homeowners’ groups, was one of the most powerful anti-growth forces in California, Morrow’s research showed. It began innocently in the 1950s, when residents living below newly developed hillsides sought stricter rules to prevent landslides. Morrow found little explicit evidence that these groups were motivated by racism, but even if all the members of this coalition had been willing to welcome neighbors of color in ensuing decades, their vehement opposition to the construction of denser housing and apartments served to keep their neighborhoods largely segregated. Many in the coalition had an earnestly held, quasi-romantic belief that a low-density city of single-family homes was the most wholesome, elevating environment and agreed that their preferred way of life was under threat. Conservatives worried that the government would destroy their neighborhoods with public-housing projects. Anti-capitalists railed against profit-driven developers. Environmentalists warned that only zero population growth would stave off mass starvation.

Much like the Reaganites who believed that “starving the beast” with tax cuts would shrink government, the anti-growth coalition embraced the theory that preventing the construction of housing would induce locals to have fewer kids and keep others from moving in. The initial wave of community plans, around 1970, “dramatically rolled back density,” Morrow wrote, “from a planned population of 10 million people down to roughly 4.1 million.” Overnight, the city of Los Angeles planned for a future with 6 million fewer residents. When Angelenos kept having children and outsiders kept moving into the city anyway, the housing deficit exploded and rents began their stratospheric rise.

Rent Burden Increasing

According to data in the National Equity Atlas, a collaboration between PolicyLink, a nonprofit in Oakland focused on advancing racial and economic equity, and the USC Equity Research Institute, almost half of all renters in the Bay Area — 48% — were rent burdened before the pandemic. This means they’re spending too big a percentage of their pay on rent.

In Oakland, 52% of all renters are rent burdened, but the burden is greatest for people color. Almost two-thirds of Black renters — 64% — are rent burdened. Next are Latinos at 55%, Native Americans at 54% and Asians at 51%.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/otisrtaylorjr/article/Bay-Area-has-been-memorable-but-family-s-15780385.php

Why? There’s not enough housing. Demand has exceeded supply. – NPR story

There are fewer homes for sale in the U.S. today than ever recorded in data going back nearly 40 years. That’s a big part of what’s driving up home prices much faster than incomes, and making homeownership less affordable for more and more Americans.

“We are simply facing a housing shortage, a major housing shortage,” says Lawrence Yun, the chief economist at the National Association of Realtors which tracks home sales. “We need to build more homes. Supply is critical in the current environment.”

The median price for previously owned homes has hit a new record at $313,000, up 16% from a year ago, the Realtors group said Thursday. There are other factors at play. Many people are buying bigger homes amid the pandemic because they are working remotely, often along with kids doing remote schooling.

The supply of previously owned single-family homes fell to a 2.4 months in October — the lowest since 1982, when the National Association of Realtors began collecting the data. National Association of Realtors

Buyers also want to take advantage of record low interest rates. But it’s very simple economics — a lack of supply pushes up prices, whether you’re talking about honeydew melons or houses.

In October, the inventory of existing single-family homes for sale dropped to 2.4 months’ worth — the lowest since records began in 1982, the NAR said.

“Housing inventory shortages have pushed national home prices considerably higher,” says Joel Kan, vice president of economic forecasting for the Mortgage Bankers Association.

“We have been under producing for the past decade,” Yun says. “We need more construction.”

After the housing crash more than a decade ago, a lot of smaller mom-and-pop homebuilders went out of business. Yun says that, together, those small companies built a lot of homes. And so that’s been playing out with anemic homebuilding ever since…

Affordable Housing

We’re talking about government subsidized housing for low-income individuals and families. Most housing advocates and opponents agree that we need more “affordable housing” in our cities. So, why don’t we have more?

It costs $750,000 to build one “affordable housing” unit in San Francisco (in 2019).

The Sacramento Bee reported that redeveloping the downtown Capitol Park Hotel into tiny, 250-square-foot units for low-income residents costs more than $445,000 per unit, higher than the median price for a detached single-family home. At $1,100 per square foot of living space, it is double what a luxury suburban home would cost.

“These are outrageous numbers, driven by bureaucratic tangles, misplaced environmental restrictions and high mandated labor costs, and unless state officials do something about them, we will never solve our housing shortage and we will continue to have shamefully high rates of poverty.”

Read more HERE: https://www.sacbee.com/opinion/california-forum/article245815115.html

Nov. 19, 2020 San Francisco Chronicle

SACRAMENTO — As California slid deeper into the housing crisis from 2015 to 2017, a state agency let $2.7 billion in bond capacity that could have been used to build affordable housing expire, according to a report from the state auditor’s office.

The blistering report, released this week, states that the bonds could have been used by developers to help build thousands more affordable housing units statewide.

State Auditor Elaine Howle said the bond allocations were mismanaged in part because California doesn’t have a clear plan on how to best use available funding for housing projects….

…But state agencies aren’t solely responsible for California’s housing failures. Auditors found that many local governments have contributed to the problem with their restrictions on development and new construction.

For example, the report states cities “can still undermine affordable housing development by using lengthy and uncertain approval processes” in many cases.

“Underdevelopment of affordable housing statewide and in certain areas is especially problematic because nearly every area in the state needs more affordable housing,” auditors stated.

The housing crisis isn’t just confined to big cities, either. In nearly every California city, at least a fifth of low-income renter households must spent 50% or more of their income on rent, the report states.

Housing in Petaluma

(Aug 16, 2021) The results of the 2020 Census are in and we now know the numbers to go with the slow growth that we see in Petaluma. Of all cities with a population of 50,000 or more, Petaluma was the fourth slowest growing city from 2010 to 2020. Petaluma grew only 3% in ten years, or .3% annual average. That’s some real foot-dragging.

Among all cities in the region with at least 50,000 people, Dublin in Alameda County saw the largest increase in residents by far — it grew by 58% since the last census in 2010, taking it from about 46,000 residents to just under 73,000 in 2020.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/These-Bay-Area-cities-grew-the-most-over-the-past-16383614.php

Dublin has been one of the fastest growing cities in California in recent years, adding thousands of units of new housing and attracting those looking for a cheaper cost of living compared to San Francisco.

Brentwood was the next highest with 24% growth since 2010, followed by Gilroy, Pittsburg and Milpitas, all in the 20% range. San Ramon, Fairfield, Pleasanton and Hayward round out the top 10 — San Ramon grew by 17%, while increases for the last three each were around 13%.

Petaluma’s Slow Growth

While Petaluma residents bemoan the building boom that is currently in process, Petaluma remains at the bottom of the heap when it comes to population growth. Petaluma grew an average .3 % per year (3% for the decade) during the decade 2010-2020, according to Census data.

Among all cities in the region with at least 50,000 people, Dublin in Alameda County saw the largest increase in residents by far — it grew by 58% since the last census in 2010, taking it from about 46,000 residents to just under 73,000 in 2020…

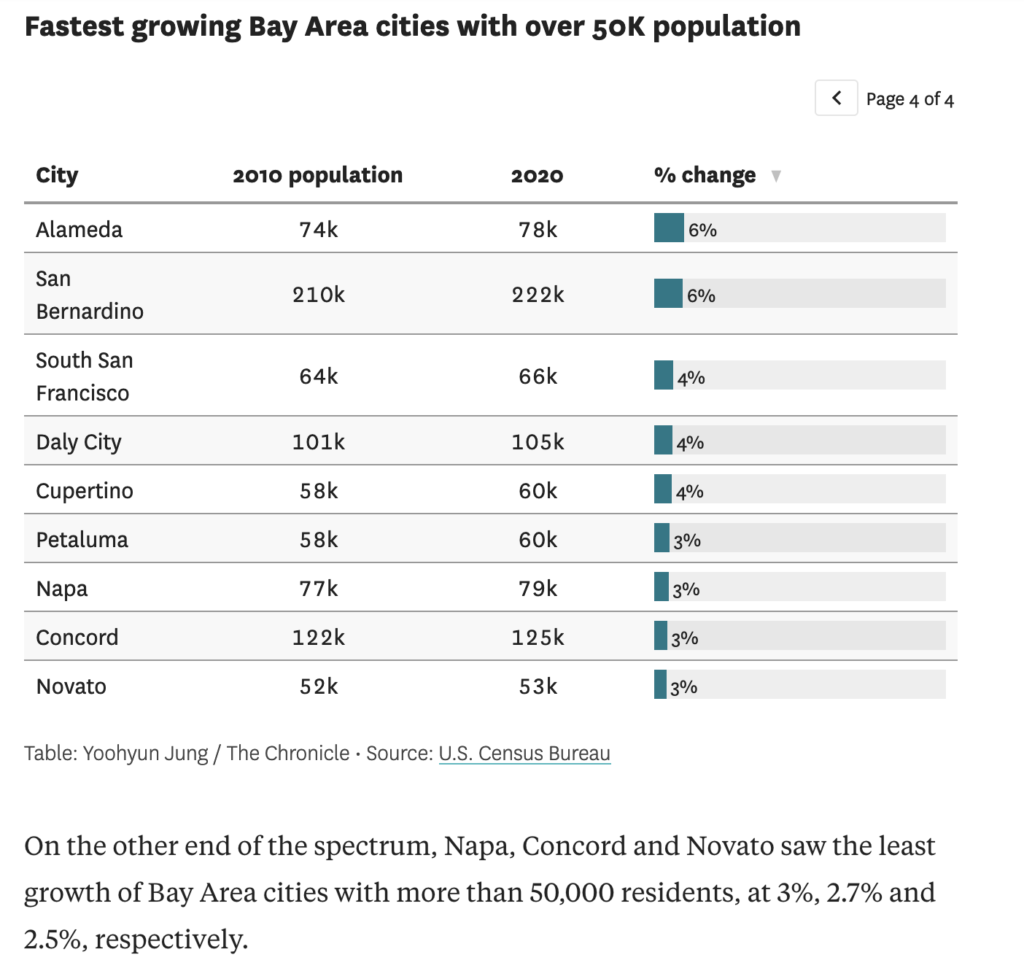

…On the other end of the spectrum, Napa, Concord and Novato saw the least growth of Bay Area cities with more than 50,000 residents, at 3%, 2.7% and 2.5%, respectively.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/These-Bay-Area-cities-grew-the-most-over-the-past-16383614.php

The following graphic (4 of 4) shows the slowest growing Bay Area cities.

Petaluma is Behind on State Affordable Housing Mandates

“Petaluma remains well behind state affordable housing mandates as it approaches its 2022 deadline, and the city will likely face new, significantly more aggressive housing targets in the next decade, according to a report on regional housing needs and new proposed construction targets.

The city’s annual Regional Housing Needs Allocation report, which was presented to city council Monday, shows Petaluma has failed to build enough affordable housing at the low and very low income levels since 2015, reaching just 18% and 47% of targets set by the regional body.”

“Sonoma County’s area median income is $102,700.

Petaluma lags in adding affordable housing, while a new plan would…

For a family of three, very low income is defined as $51,150 a year, and low income equates to $81,850.

For single-person households, those who earn less than $86,300 are considered below moderate income, with very low and low-income earners making between $39,800 and $63,650 per year.”

Restrictive zoning keeps Marin the most segregated county in the Bay Area

J.K. Dineen Dec. 8, 2020 Updated: Dec. 8, 2020 SF Chronicle

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Restrictive-zoning-keeps-Marin-the-most-15782840.php

While multifamily development doesn’t guarantee an integrated neighborhood, the study shows that in a wealthy county like Marin, where the average home price is just under $1.3 million, strict single-family zoning all but ensures that communities will remain wealthy and white…

“In diverse areas like the Bay Area, if you have all-white communities, what that means is you have an all non-white community somewhere else,” said lead researcher Stephen Menendian, assistant director of the UC institute. “Marin County regards itself as a progressive place, but it doesn’t live up to its values. You can’t deny it if you look at the data.”…

“Every time we start talking about housing they use the environmental argument to stop the development,” Carrera said. “It makes me wonder if it’s an elegant way to be to maintain the current segregation and the overcrowding, which is a result of the lack of housing opportunity.”

Petaluma’s NIMBYs

Good column about city politics and the nextdoor.com NIMBYs, by John Burns in the Petaluma Argus-Courier.

https://www.petaluma360.com/article/opinion/community-matters-development-fuels-petaluma-political-divide/

Here are the closing paragraphs:

Let’s face it: Nobody in Petaluma wants to “pave paradise,” as Joni Mitchell sang so eloquently. That’s completely understandable, and very few enjoy construction noise or more traffic.

But for moral, economic and social justice reasons, some new housing construction is necessary in Petaluma, particularly to house lower income-families. Many people who work in Petaluma, including teachers, nurses, tradespeople and service sector workers such as restaurant and hotel employees, commute long distances because they cannot afford to live here. Many lower-income people, including Latinos, suffer chronic housing instability with overcrowding and the constant threat of eviction, a situation that creates stress, depression and hopelessness for too many families.

Creating permanent housing for the chronically homeless is a moral imperative and produces significant savings in the healthcare and public safety systems.

All of the white, highly privileged, liberal Democrats currently serving on the Petaluma City Council enjoy living in their own homes. How progressive is it for them to deny housing to those who don’t happen to share such privilege?

Housing Projects: City of Petaluma page: https://cityofpetaluma.org/planning-major-developments/

Hines Project – 402 housing units proposed next door to the downtown train station. – proposed Hines Project at the downtown SMART Station…proposed to be five stories, 402 multi-family units and 622 parking spaces.

Haystack Project was approved between Copeland and Weller Street. – four stories, 178 housing units and 24,855 square feet of ground floor commercial. That project may be temporarily stalled…

https://nextdoor.com/p/fHgkHhqLFPdD?view=detail

Petaluma’s Corona Station project scrapped

https://www.petaluma360.com/article/news/petalumas-corona-station-project-scrapped/

Housing opponents succeeded in nixing the Corona Station project that would have built 110 single family homes near the SMART rail corridor at Corona Road and North McDowell Boulevard.

“The decision also has a domino effect as developers are enmeshed in a complex array of agreements linking the second SMART station, an affordable housing development and a 400-unit proposed apartment complex downtown…

In total, last week’s decision reverses approvals on the single-family Corona Station residential project, the dedication of a 2.5-acre site for affordable housing and approvals satisfying affordable housing requirements associated with the 400-unit Downtown Station project.”

Essentially, the NIMBYs shut down scores of affordable housing units – all in the interest, they say, of affordable housing. Maybe they will get their 100% affordable project that has no impact on traffic, water, the environment or Petaluma’s “charm,” but it’s doubtful. Who will build it, if not developers? Any new project is going to cost significantly more money because of pandemic related rise in the cost of building materials. Bottom line: NIMBYs are preventing affordable housing as well as badly needed market-rate housing.

CA State Legislation

SF Chronicle, Dec. 8, 2020.

California lawmakers try again to make it easier to build housing.

a new bill called SB9, is once again part of a legislative package on housing that Atkins said she plans to unveil this week. While lawmakers can introduce bills, the regular business of the Capitol does not resume until January.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/politics/article/California-lawmakers-try-again-to-make-it-easier-15783955.php

“We’re starting at a good place,” Atkins said. “There may be a few new ideas I’ve heard of.”

Several other old ones also resurfaced Monday.

Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco, reintroduced his “gentle density” measure that would allow cities to rezone residential parcels for apartment or condominium projects of up to 10 units without having to go through environmental reviews that can add years to the process. Under his bill, SB10, cities could adopt the change for neighborhoods near public transit and in high-income areas with access to jobs and good schools, but would not be required to.

“It’s a powerful new tool for cities,” he said. “We make it really painful, expensive and lengthy for cities to do the right thing.”

Are Nimbys Losing Power?

The tide is shifting from local control of development to state control. Read

Twilight of the NIMBY

Suburban homeowners like Susan Kirsch are often blamed for worsening the nation’s housing crisis. That doesn’t mean she’s giving up her two-decade fight against 20 condos.

NIMBY stands for “Not in my backyard,” an acronym that proliferated in the early 1980s to describe neighbors who fight nearby development, especially anything involving apartments. The word was initially descriptive (the Oxford English Dictionary added “NIMBY” in 1989 and has since tacked on “NIMBYism” and “NIMBYish”) but its connotation has harshened as rent and home prices have exploded. NIMBYs who used to be viewed as, at best, defenders of their community, and at worst just practical, are now painted as housing hoarders whose efforts have increased racial segregation, deepened wealth inequality and are robbing the next generation of the American dream.

It seems like a lot to dump on what amount to hyperlocal disputes that largely consist of homeowners trekking down to city hall to complain about a new condominium building or proposed row of townhomes. But take a step back: What’s at stake in these disputes is the structure of American civilization. In a country with little national housing policy, the thicket of zoning, environmental and historic preservation laws that govern local land use are the primary regulators of a multi-trillion-dollar land market that is the source of most households’ wealth and form the map for how the nation’s economy and society are laid out…

Read https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/05/business/economy/california-housing-crisis-nimby.html

Sonoma County residents with a library card can get a free two-day pass to read the NYT online here: https://sonomalibrary.org/online-news

Recommended Reading:

Generation Priced Out Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America, by Randy Shaw (Author) @beyondchron on Twitter

Generation Priced Out is a call to action on one of the most talked-about issues of our time: how skyrocketing rents and home values are pricing the working and middle classes out of urban America. Randy Shaw tells the powerful stories of tenants, politicians, homeowner groups, developers, and activists in over a dozen cities impacted by the national housing crisis. From San Francisco to New York, Seattle to Denver, and Los Angeles to Austin, Generation Priced Out challenges progressive cities to reverse rising economic and racial inequality.

Shaw exposes how boomer homeowners restrict millennials’ access to housing in big cities, a generational divide that increasingly dominates city politics. Shaw also demonstrates that neighborhood gentrification is not inevitable and presents proven measures for cities to preserve and expand their working- and middle-class populations and achieve more equitable and inclusive outcomes. Generation Priced Out is a must-read for anyone concerned about the future of urban America.